Light

The Sacred Coca Leaf is an ancestral legacy , food for the body and soul, a bridge between worlds .

It is a living ritual, a green memory that has sustained people for millennia.

This space is to honor its essence, recover its luminous wisdom , and restore its place in the sacred fabric of existence.

Nutrition

and Medicine

In traditional Andean medical practice, the coca leaf is used as an oracle to divine the patient's condition. Coca plays an important role in the healing process due to its many medicinal properties , such as soothing stomach pains by drinking its leaves as tea, and using them in poultices for bruises, fractures, and inflammation, toothaches, headaches, and other ailments. Coca leaf flour can be consumed in larger doses with food; its high calcium and iron content helps with diseases such as Parkinson's, osteoporosis, and anemia.

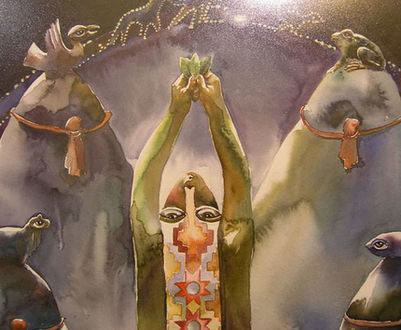

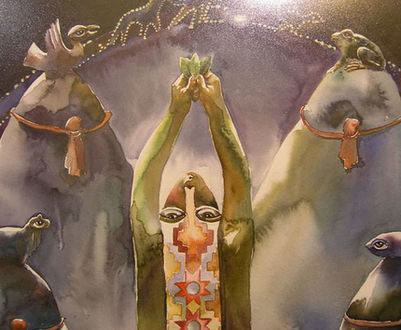

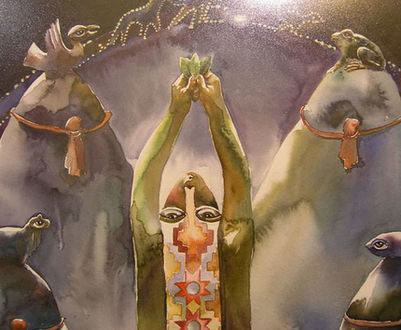

Worldview

%2015_46_13.png)

Go to the next tab to read more.

Among the indigenous peoples of the Americas, some still practice their ancestral rituals. In Peru, the highest-living tribes are the Qero nation , located near the Ausangate snow-capped mountain in the province of Cusco. Among their most important rituals is the Haywarikuy , called despacho, an offering to the earth. Its performance is related to the Andean agricultural calendar; as a reciprocal act, we return to the earth what it gives us , in order to maintain the natural order and continue receiving good harvests and good times, based on Ayni (reciprocity), a fundamental concept in the Andean worldview. This ceremony consists of offering the earth various elements, each with a unique symbolism: seeds, corn, chicha, wine, sweets, animal fats, etc.; among its many elements, coca leaves are the most important, as they are the bridge between heaven and earth. The best leaves are selected and arranged like fans to be kintus with which prayers are offered to the Apus (mountains) and the earth.

The coca leaf has an anatomy that is analogous to the human body, so rounded leaves can indicate femininity, while longer leaves indicate masculinity. The right or left side of the body is similar to the leaf, and there are also indicators based on special leaf formations that can represent illness, success, money, etc. Each leaf has its own meaning.

To perform the reading, leaves in good condition are selected; the person reading puts their breath on it, transmitting their human warmth so the coca doesn't get cold. The coca leaves are spread out on the uncuña (a small, woven blanket specially designed for coca), and three leaves are chosen, which will serve as the base for the reading . There are several ways to read. Generally, if the leaves fall in a row and most of them fall on the front side, it means the answer is positive. If most of the leaves fall on the back, the answer is negative. Depending on the position of the leaves in relation to each other, everything spoken appears like a map of the heart , like a set of past or future events.

Plant anatomy and field.

Go to the next tab to read more.

Coca is a small shrub that grows from 70 cm to 2 meters tall. It has woody stems and deep green leaves, small white flowers, and red fruits that have no pulp as they contain the seed.

It grows well in the warm and humid lands near the Andes mountain range at an altitude range from 500 to 2000 meters above sea level.

Coca leaf cultivation, along with corn and cocoa, is one of the oldest in the American continent, and some ancestral rituals still survive for its work.

First, the seedbed is made with its ripe fruit/seed, fermented for a week in something moist (banana leaves or cloth) to sow it in the ground and 1 year later it can be transplanted into its land, called a table (1000m2), where a crowbar is used to ensure the depth of its root in the ground, in addition to the cebador, a stick that compacts the earth around, to secure the template. It is from the following year that its harvest begins, under the coca waranchi ritual, where its first leaves are received, ceremonially, on colorful blankets, along with flowers and streamers, where the owners of the farm together with their neighbors, ch'allan and propitiate its successful production, for the following years of life (between 30 and 100 years).

During this time, weeding and harvesting are carried out 3 to 4 times per year, a group effort carried out using the ayni system (organized by neighbors who take turns working together on each of their plots).

After each harvest, the leaf must be dried in a single spread in the matocancha (flat stone drying room) to prevent it from turning black.

To preserve its texture and flavor, for pijchado, while it is drying, and when it is still soft, it is covered and crushed several times, a technique known as "coca saruy", a leaf that becomes flatter so it can be bagged and transported.

Coca plantation does not require any fertilizer or even irrigation, and can grow on steep terrain where other crops do not grow. The only thing it requires is weeding/hoeing with the kituchi, a hand tool with its curved iron fork, which uproots all kinds of wild plants that grow around it, decomposing and nourishing the soil, as well as oxygenating it.

All this work requires a great deal of effort, which must be compensated in full for the farmers, in order to avoid the use of herbicides and chemical fertilizers, which simplify their work but contaminate the plant. That's why it's important for us, as consumers, to take care of the coca growers so that they can take care of the coca agroecologically, and so that it, in turn, can take care of us with its beneficial medicinal nutrients. This is why monocultures should not be encouraged, but rather integrated crops, where crops are combined, within or around cassava, corn, and beans, among others.

Art and culture

%2011_01_07.png)

Soon

Archaeology

Go to the next tab to read more.

As Ciro Alegría narrates in his book in 1941, the world is wide and alien:

“Coca is good for hunger, for thirst, for fatigue, for heat, for cold, for pain, for joy… It is good for life… With coca, one gives gifts to the enchanted hills, lakes, and rivers; with coca, the living live; carrying coca in one's hands, the dead depart…”

This is a reminder of the importance of this plant's use in rites of passage as well as in everyday life. Evidence of this is found in mortuary remains where the person carries a chuspa (a special bag for coca) and/or coca leaves in their mouth, dating back 8,000 years.

In Peru, Ecuador, Bolivia, and Colombia, archaeological ceramic pieces from pre-Inca cultures have been found. The main representations are of human/animal figures holding lime kegs, chuspas containing coca, and a protuberance on the cheek representing the chewing of the leaf.

Colombia has archaeological artifacts of poporos, complete pieces of gold jewelry, and also gourds with gold appliqués.

The poporo is a ceremonial container used to store sea snail lime in combination with coca leaves in rituals. Natural gourds are still used today as poporos, and they are a central element in the cultural identity of the indigenous peoples of the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta.

In several Andean-Amazonian communities in South America, various rituals involving the coca leaf and the use of accompanying elements remain in place: chuspas, caleros, and uncuñas. Coca was and continues to be the mother plant that sustained people and their communities in physical and spiritual integrity.